Source country taxation, the environment and oil rigs

Last week sometime I found myself in a Twitter discussion with PEPANZ – of all people – as they were saying the TWG had supported the recent extension of the tax exemption for oil rigs. It is an exemption that is theoretically timelimited for non-resident companies involved in exploration and development activities in an offshore permit area. Theoretically because it will have been in force for 20 years if it actually does expire this time.

Having been a little involved with the TWG – as well as the Treasury official on the last rollover – I was somewhat surprised by PEPANZ’s comment. But in the end they were referring to an Officials paper for the TWG rather than a TWG paper per se. A subtle and easily missed difference.

And one they unfortunately also made in their submission to the Finance and Expenditure Committee (1). Although it was a little odd that they needed to make a submission as everyone has known for 5 years that the exemption was expiring.

But in that thread PEPANZ encouraged people to read the Cabinet paper and so for old time sake I did. The analysis was quite familiar to me but the thing that gave me pause was the fiscal consequences were said to be positive.

Yes positive.

Implementing a tax exemption would increase the tax take. A veritable tax unicorn.

No wonder it had such support. I guess this exemption will now have to come off the tax expenditure statement.

Personally I am not a fan of this exemption or its extension. And although I accept the prevailing arguments – much like the difference between a paper for the TWG and a paper of the TWG – it is less clear cut than it seems.

International framework for taxing income from natural resources

Now followers of the digital tax debate will know all about how source countries can tax profits earned in their country if these profits are earned through a physical presence in their country aka permanent establishment. And because it is super easy to earn profits from digital services without a permanent establishment there is a problem.

However for land or natural resource based industries a physical presence is – by definition – super easy.

And if you properly read treaties there is a really strong vibe through the individual articles that source countries keep all profits from its physical environment (2) while returns from intellectual property belong to the residence or investor country.

So before tax fairness or stopping multinational tax evasion was a thing, there was source country taxing rights based on natural resources.

Then to make it super super clear Article 5(2)(f) of the model treaty makes a well or a mine a permanent establishment just in case there was any argument.

To be fair to our friends the visiting oil rigs, other than the physical environment vibe there is no actual mention of exploration in the model article. But the commentary says it is up to individual countries how they wish to handle this. (3)

What does New Zealand do?

The best one to look at is the US treaty. In that exploration is specifically included as creating a permanent establishment but periods of up to 6 months are also specifically excluded (4).

This is interesting for two reasons.

First the negotiators of the treaty clearly specifically wanted exploration to create a taxing right as this paragraph is not in the model treaty. Secondly it stayed in the treaty even after a protocol was negotiated in 2010. That is if this provision and the 6 month carve out were a ‘bad’ thing for New Zealand it would have made sense for it to have come out at that point. Either unilaterally or as a tradeoff for something else.

So in other words anything to do with the taxation of oil rigs involved in exploration cannot be considered to be a glitch with the treaty that could be fixed with renegotiation. Unless of course it was oversight in the 2010 negotiations.

What are the facts?

The optimal commercial period for these rigs to be in New Zealand seems to be about 8 months. That is two months or so too long to access the exemption. But rather than pay tax they will leave and another rig will come in with associated extra costs and environmental damage.

This is what was happening before the exemption came into place in 2004 and so does prima facie seem a reasonable case for just having an outright exemption. However:

The 2019 Regulatory Impact Statement says that the contracts have a tax indemnity clause meaning that any tax payable by the non-resident company must be paid by the New Zealand permit holder. (5)

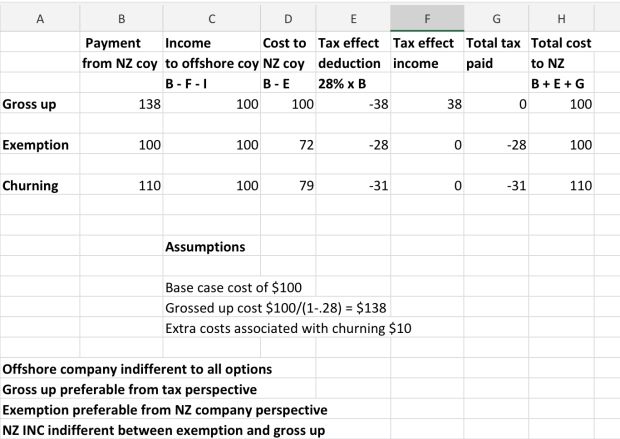

This means that the outcomes would be broadly similar to this table. This is on the basis that rigs could be substituted albeit with delay at additional cost rather than exploration simply being deferred to another year. (6)

Why don’t I like the exemption?

Much like the difference between TWG reports and reports for the TWG it is all pretty nuanced.

Pre 2004, as there were tax indemnities, the only reason to have the rigs leave and another one come in was if the cost to the company of the churning was less than the cost – paying the tax – of the rig staying put.

However while that would be a completely reasonable business decision for the company it is highest cost for the country as a whole and the highest cost to the tax base of all the options.

And so the argument for an exemption was framed. An exemption lowers the cost to the Crown and also to the company. Win Win.

However the tax base does best in a world without the exemption but where the rigs stay put and the company pays the non-resident operators tax.

Now requiring that would be somewhat stalinist but it does feel that Government has had its hand forced when it wasn’t party to any of the original decisions. The Government has no control over the cost structure of the industry but:

- Needs to exempt income of a class of non-resident at a time when it is looking to expand taxing rights over other non-residents;

- Weakens its claim on the tax base associated with natural resources,

- Gets offside with a major stakeholder of its confidence and supply partner.

And all of this is before you get to the precedential risk associated with moving away from the otherwise broad base low rate framework. Which by definition involves winners and losers.

I am also not convinced by the revenue positive argument. The RIS states that as the exemption has been going on forever the forecasts have already factored in the exemption (7). This means an extension of the exemption has no fiscal effect.

However by the time it gets to the Cabinet Paper – albeit close to a year after the RIS was signed off – a $4 million cost of not extending the exemption has now been incorporated into the forecasts (8). And so – hey presto by extending the exemption – an equivalent revenue benefit arises that can go on the scorecard (9). From which other revenue negative tax policy changes can be funded.

Every Minister of Revenue’s dream.

So like I said – not a fan. There is a narrow supporting argument. Absolutely. But the whole thing makes me very uncomfortable. To make matters worse – it is only extended for 5 years. It hasn’t been made permanent. Even after 20 years. SMH.

Hope I am doing something else in 5 years time.

Andrea

(1) Curiously officials write up of the submission in the Departmental report page 171 is far more fulsome than the written submission. I guess it must reflect an empassioned verbal submission from PEPANZ.

(2) Article 6 of the model treaty makes this explicit without any reference to a permanent establishment.

(3) Paragraph 48 Page 128

(4) Article 5(4)

(5) Paragraph 6. This comment isn’t the the recent RIS but as the analysis is based around the New Zealand permit holder wearing the additional costs associated changing the non-resident operator it is reasonable to assume that equivalent clauses are in the new contracts.

(6) Section 2.3 of RIS discusses the delays associated with changing operators.

(7) Page 11

(8) Paragraphs 21-23

(9) Section 4.6

Taxing multinationals (3) – Digital Services Tax

I had thought this might be a good post for my young friends to sub in on. But quite quickly into the conversation it became clear there would need to be too many ‘but Andrea says’ interjections to make it technically right. So we decided that I should go it alone.

Background

Now first of all the whole making multinationals pay tax thing is a bit of a comms mess so I thought I’d have a go at unpicking it.

The underlying public concern was, and is, based around large – often multinational – companies not paying enough tax. A recent article on my Twitter feed on Amazon earning $11.2 billion but paying no tax is pretty representative of the underlying concern.

Technically there were/are two reasons for this:

1) The ability to earn income without physically being in the country you earn the money from. This is primarily the digital issue.

2) Arbitraging and finding their way through different countries rules to overall lower tax paid worldwide. This is primarily an issue with foreign investment as such techniques really only worked with locally resident companies or branches.

In terms of the OECD work while it was 1) that kicked off the work – most of their action points have previously related to 2). That is – the base erosion part of base erosion and profit shifting.

In New Zealand there was a 2017 discussion document that was advanced by Judith Collins and Steven Joyce on the New Zealand specific bits of 2) which was then picked up and implemented by Stuart Nash and Grant Robertson.

And while the speech read by Michael Wood after Speaker Trevor got upset with Stuart for sitting down opens with a discussion of ‘the digital issue’, the bill was about increasing the taxation of foreign investment – ie 2) – not the tech giants. (1)

Current NZ proposal

Now Ministers Robertson and Nash have issued a discussion document proposing – maybe – a digital services tax if the OECD doesn’t get its act together.

Before we go any further one very key aspect here is the potential revenue to be raised. $30- $80 million dollars a year.

Now that may seem like a lot of money – and of course it is – but not really in tax terms. As a comparison $30 million was the projected revenue from a change to the employee shares schemes. Only insiders and my dedicated readers would even have been aware of this.

Now given the public concern and the size of the tech giants – with $30 million projected revenue – I would say either there really isn’t a problem or the base is wrong.

So what is the base? What is it that this tax will apply to?

Much like the Michael Wood/Stuart Nash speech, the problem is set out to be broad – digital economy including ecommerce (2) but then the proposed solution is narrow – digital services which rely on the participation of their user base (3).

This tax will apply to situations where the user is seen to be creating value for the company but this value is not taxed. The examples given are the content provided for YouTube and Facebook , the network effects of Google or the intermediation platforms of Uber and AirBnB.

And because of this, the base for the tax is the advertising revenue and fees charged for the intermediation services. Contrary to what the Prime Minister indicated it will not be taxing the underlying goods or services (4). It will tax the service fee of the Air BnB but not the AirBnB itself. That is already subject to tax. Well legislatively anyway.

There are some clever things in the design as, to ensure it doesn’t fall foul of WTO obligations, it applies to both foreign and New Zealand providers of such services. But then sets a de minimis such that only foreign providers are caught (5).

Officials – respect.

But then it takes this base and applies a 2-3% charge and gets $30 million. Right. Hardly seems worth it for all the anguish, compliance cost and risk of outsider status.

The other issue that seems to be missing is recognition of the value being provided to the user with the provision of a free search engine, networking sites, or email. In such cases while the user does provide value to the business in the form of their data, the user gets value back in the form of a free service.

For the business it is largely a wash. They get the value of the data but bear the cost of providing the service. That is there is no net value obtained by the business. (6)

For the individual the way the tax system works is that private costs are non deductible but private income is taxable. Yep that is assymetric but without assymetries there isn’t a tax base.

In some ways this free service is analogous to the free rent that home owners with no mortgage get – aka an imputed rent and the associated arguments for taxing it. That is the paying of rent is not deductible but the receipt of rent should be taxable.

Under this argument it is the user that should be paying tax on the value that has been transferred to them via the free service not the business. While I think the correct way to conceptualise digital businesses, taxing users is as likely as imputed rents becoming taxable.

But key thing is that the tax base is quite narrow and doesn’t pick up income from the sale or provision of goods and services from suppliers such as Apple, Amazon and Netflix. None of this is necessarily wrong as there has never been taxation on the simple sale of goods but it is a stretch to say this will meet the publics demand for the multinationals to pay more tax.

And it is true such sales are subject to GST but last time I looked GST was paid by the consumer not the business.

Technically there are also a number of issues.

The tax won’t be creditable in the residence country because it is more of a tariff than an income tax hence the concern with the WTO. It is also a poster child for high trust tax collecting as the company liable for the tax by definition has no presence in New Zealand and it is also reliant on the ultimate parent’s financial accounts for information.

This is all before you get to other countries seeing the tax as inherently illegitimate and risking retaliation.

OECD proposals

The alternative to this is what is going on at the OECD.

They have divided their work into 2 pillars.

Pillar one

Pillar one is about extending the traditional ideas of nexus or permanent establishment to include other forms of value creation.

The first proposal in this pillar is to use user contribution as a taxing right. It is similar to the base used for the digital services tax and faces the same conceptual difficulty – imho – with the value provided to users.

However unlike the DST it would be knitted into the international framework, be reciprocal and there would/should be no risk of retaliation or double taxation.

The second proposal is to extend a taxing right based on the marketing intangibles created in the user or market country. The whole concept of a marketing intangible is one I struggle with. Broadly it seems to be the value created for the company – such as customer lists or contribution to the international vibe of the product – from marketing done in the source/user/market jurisdiction.

This is a whole lot broader than the user contribution idea and has nothing really to do with the digital economy – other than it includes the digital economy.

Some commentators have suggested it is a negotiating position of the US. Robin Oliver has suggested that the US seems to be saying – if you tax Google we’ll tax BMW. In NZ what this would mean is that if we could tax Google more then China could tax Fonterra more based on marketing in China that supported the Anchor brand.

Both options explicitly exclude taxation on the basis of sales of goods or services (7).

There is a third option under this option pithily known as the significant economic presence proposal. The Ministers discussion document describes it essentially as a form of formulary apportionment that could be an equal weighting of sales, assets and employees. (8) Now that sounds quite cool.

I do wonder whether it would also be reasonable to include capital in such an equation as no business can survive without an equity base.

In the OECD discussion document they state that while revenue is a key factor it also needs one or more other things like after sales service in the market jurisdiction, volume of digital content, responsibility for final delivery or goods (9). Such tests should catch Apple and Amazon in Australia as they have a warehouse there but they are likely to be caught already with the extension of the permanent establishment rules.

It is less clear whether this would mean New Zealand could tax a portion of their profits but if that is what is wanted – this seems the best option as it is getting much closer to a form of formulary apportionment.

Pillar two

The other pillar – Pillar 2 – sets up a form of minimum taxation either for a parent when a subsidiary company has a low effective tax rate or when payments are made to associated companies with low effective tax rates. Again much broader than just the digital economy and similar to what I suggested a million years ago as an alternative to complaining about tax havens.

For high tax parents with low tax subsidiaries this is effectively an extension of the controlled foreign company rules and would bring in something like a blacklist where there could be full accrual taxation or just taxation up to the ordained minimum rate.

For high tax subsidiaries making payments to low tax sister or holding companies, they have the option of either denying a tax deduction for the payment or imposing a withholding tax. This could be useful in cases where royalties and the like are going to companies with low effective tax rates. On the face of it, it could also apply to payments for goods and services made by subsidiary companies.

It might also be effective against stories of Amazon not paying any tax – as zero is a pretty low effective tax rate.

The underlying technology seems to be based on the hybrid mismatch rules which also had an income inclusion and a deduction denial rule. Such rules were ultimately aimed at changing tax behaviour rather than explicitly collecting revenue.

Pillar 2 seems similar. If there will be clawing back of under taxation it is better to have no under taxation in the first place. So it may mean the US starts taxing more rather than subsidiary companies paying more tax.

Pillar 2 by being based around payments within a group will have no effect when there is no branch or subsidiary as is often the case with the cross border sale of goods and services to individuals .

My plea

Now the reason for all this work – both the DST and the OECD – is the issue of tax fairness and the public’s perception of fairness.

DST – imho – is really not worth it. All that risk for $30 million per year. No thank you.

But it has come about because even after the BEPS changes they still aren’t catching the underlying concern of the public – the lack of tax paid by the tech giants.

And there is no subtlety to that concern. In all my discussions no one is separating Apple, Amazon and Netflix from Google, Facebook and YouTube.

But it is time to be honest.

There are good reasons for that distinction. NZ is a small vulnerable net exporting country. Our exporters may also find themselves on the sharp end of any broader extension of taxation.

So policy makers please stop asserting the problem is the entire digital economy and then move straight to a technical discussion of a narrow solution without explaining why.

It gives the impression that more is being done than actually is. And quite frankly this will bite you on the bum when people realise what is actually going on.

And front footing an issue is Comms 101 after all.

Andrea

(1) To be fair that bill did also include a diverted profits tax light which was directed at the likes of Facebook who just do ‘sales support’ in New Zealand rather than full on sales. But that was a very minor part of the bill.

(2) Paragraphs 1.2-1.4

(3) Paragraphs 1.5 onwards

(4) I had a link for her press conference but it has been taken down. She suggested that it was only fair that if motels in NZ paid tax so should AirBnBs. I completely agree but the AirBnBs are already in the tax base and if they aren’t currently paying tax that is an enforcement issue not a DST issue.

(5) Paragraph 3.24

(6) Paragraph 60 of the OECD interim report also notes this issue.

(7) Paragraph 67

(8) Paragraph 4.47

(9) Paragraph 51

Taxing multinationals (2) – the early responses

Ok. So the story so far.

The international consensus on taxing business income when there is a foreign taxpayer is: physical presence – go nuts; otherwise – back off.

And all this was totally fine when a physical presence was needed to earn business income. After the internet – not so much. And with it went source countries rights to tax such income.

Tax deductions

However none of this is say that if there is a physical presence, or investment through a New Zealand resident company, the foreign taxpayer necessarily is showering the crown accounts in gold.

As just because income is subject to tax, does not necessarily mean tax is paid.

And the difference dear readers is tax deductions. Also credits but they can stand down for this post.

Now the entry level tax deduction is interest. Intermediate and advanced include royalties, management fees and depreciation, but they can also stand down for this post.

The total wheeze about interest deductions – cross border – is that the deduction reduces tax at the company rate while the associated interest income is taxed at most at 10%. [And in my day, that didn’t always happen. So tax deduction for the payment and no tax on the income. Wizard.]

Now the Government is not a complete eejit and so in the mid 90’s thin capitalisation rules were brought in. Their gig is to limit the amount of interest deduction with reference to the financial arrangements or deductible debt compared to the assets of the company.

Originally 75% was ok but then Bill English brought that down to 60% at the same time he increased GST while decreasing the top personal rate and the company tax rate. And yes a bunch of other stuff too.

But as always there are details that don’t work out too well. And between Judith and Stuart – most got fixed. Michael Woodhouse also fixed the ‘not paying taxing on interest to foreigners’ wheeze.

There was also the most sublime way of not paying tax but in a way that had the potential for individual countries to smugly think they were ok and it was the counterparty country that was being ripped off. So good.

That is – my personal favourite – hybrids.

Until countries worked out that this meant that cross border investment paid less tax than domestic investment. Mmmm maybe not so good. So the OECD then came up with some eyewatering responses most of which were legislated for here. All quite hard. So I guess they won’t get used so much anymore. Trying not to have an adverse emotional reaction to that.

Now all of this stuff applies to foreign investment rather than multinationals per se. It most certainly affects investment from Australia to New Zealand which may be simply binational rather than multinational.

Diverted profits tax

As nature abhors a vacuum while this was being worked through at the OECD, the UK came up with its own innovation – the diverted profits tax. And at the time it galvanised the Left in a way that perplexed me. Now I see it was more of a rallying cry borne of frustration. But current Andrea is always so much smarter than past Andrea.

At the time I would often ask its advocates what that thought it was. The response I tended to get was a version of:

Inland Revenue can look at a multinational operating here and if they haven’t paid enough tax, they can work out how much income has been diverted away from New Zealand and impose the tax on that.

Ok – past Andrea would say – what you have described is a version of the general anti avoidance rule we have already – but that isn’t. What it actually is is a form of specific anti avoidance rule targetted at situations where companies are doing clever things to avoid having a physical taxable presence. [Or in the UK’s case profits to a tax haven. But dude seriously that is what CFC rules are for]

It is a pretty hard core anti avoidance rule as it imposes a tax – outside the scope of the tax treaties – far in excess of normal taxation.

And this ‘outside the scope of the tax treaties’ thing should not be underplayed. It is saying that the deals struck with other countries on taxing exactly this sort of income can be walked around. And while it is currently having a go at the US tech companies, this type of technology can easily become pointed at small vulnerable countries. All why trying for an new international consensus – and quickly – is so important.

In the end I decided explaining is losing and that I should just treat the campaign for a diverted profits tax as merely an expression of the tax fairness concern. Which in turn puts pressure on the OECD countries to do something more real.

Aka I got over myself.

In NZ we got a DPT lite. A specific anti avoidance rule inside the income tax system. I am still not sure why the general anti avoidance rule wouldn’t have picked up the clever stuff. But I am getting over myself.

Of course no form of diverted profits tax is of any use when there is no form of cleverness. It doesn’t work where there is a physical presence or when business income can be earned – totes legit – without a physical presence.

And isn’t this the real issue?

Andrea

Taxing multinationals (1) – The problem

It is seriously odd being out of the country when seminal events occur.

On that Friday I was in London. Waking at 4.30 am and checking Facebook. Just coz.

My Christchurch based SIL posted that she was relieved now she had picked up her kids from school. Sorry what? Thinking there might have been another earthquake I checked the Herald app.

Oh right.

In the swirl of issues has come the suggestion Facebook and Google should be taxed into compliance. Of course a boycott could be equally effective. Except if users of Facebook are anything like your correspondent and there is inelastic demand. Possibly not at insulin levels but until demand changes I am not sure taxation would be that effective.

But the whole issue of tax and Facebook, Google and Apple has been a running sore for many years now and so I thought I’d take a bit of time to go through the background of it all. [Really keen readers though could search Cross border taxation on the panel on the right for more detail]. Future posts will look at what is being proposed as a solution in New Zealand and by the OECD.

Background to the background

The international tax framework since like forever aka League of Nations – before even I was born – has been that the country that the taxpayer lives in or is based in – residence country – can tax all the income of that taxpayer. Home and abroad – all in.

Where it gets tricky is the abroad part. As the foreign country, quite reasonably, will want to tax any income earned in its country – source country.

So the deal cut all those years ago – and is the basis of our double tax treaties – was:

For business income the source country gets first dibs if the income was earned through the foreign taxpayer physically being in their country – office, factory etc. Rights to tax were pretty open ended and the residence country of the taxpayer would give a credit for that tax or it would exempt the income.

So far so good.

Except if there were no physical presence then there was no taxing rights. But in League of Nations times – or even relatively recently like when I first went to work – the ability to earn business income in a country without an office or factory was pretty limited. So as constraints go – it kind of went.

For passive income like interest, dividends, and royalties the source country could tax but the rate of tax was limited. 10-15% was standard. And again the residence country gave a tax credit for that tax or exempted the income.

Presenting problem

Looking now at our friends Apple, Google and Facebook. Apple provides consumer goods and Google and Facebook provide advertising services.

When your correspondent started work, foreign consumer goods arrived in a ship, were unloaded into a warehouse and then onsold around the country. Such an operation would have required a New Zealand company complete with a head office, chief executive and a management team. All before you got to getting the goods to shops to sell.

Such an operation would most likely have involved a New Zealand resident company. Even if it didn’t no one would be arguing about a physical presence of a foreign company as – to operate in New Zealand – it would have needed more physical presence than Arnold Schwarzenegger. And yes both creatures of the eighties.

For advertising services, no ships involved but people on the ground hawking classified and other ads for newspapers. Again more physical presence than Princess Di. [Getting to the point – promise – as am now running out of 80’s icons]

Now internet enter stage left.

For goods consumers now don’t need to go to a shop. iPads and iPhones bought on line. Physical presence non existent along with (income) taxing rights.

For services – more interesting. Still seems to be some presence but like – sales support – not like completing contracts. So no taxable presence and no (income) taxing rights.

At this point the Tax Justice outrage, BEPS and the Matt Nippert articles started. The UK and Australia brought in a diverted profits tax and our government did something.

Phew. So everything is ok now.

So why then is the Government making announcements and the OECD still doing stuff?

Next post. Promise.

Andrea

When Harry met FATCA

Let’s talk about tax.

Or more particularly let’s talk about the taxation of US citizens living abroad.

I just love the Royal Family. Yeah I know it goes against any and every possible progressive and egalitarian ideal I hold but phish.

I grew up reading my grandmother’s Women’s Weekly and their coverage of Princess Anne’s (first) wedding and the Silver Jubilee. Over time this progressed to Diana, Fergie and their babies. And the Womens Weekly became the Hello magazine. Complete with Princess Beatrice aged two at a society wedding. So good.

And season two of The Crown has landed. Brilliant. I mean seriously- what about Philip?

Of course season one was dominated by the spectre of the abdication of a King who wanted to marry a divorced American woman. As well as the sister of the Queen who wanted to marry a divorced man.

So it was with every sense of delighted irony that I watched the recent engagement of Prince Harry to a divorced older mixed race American woman. Whose father might be catholic. ROFLMAO.

And my delight became complete when the Washington Post pointed out Meghan and Harry’s children will be subject to FATCA and US residence taxation. Oh and I have been meaning to write about the joys of US citizen taxation since like forever. So finally here was my angle.

The British Royal family – the gift that keeps on giving.

First key thing is that all people born in the United States or born to at least one US parent – like Harry’s children will be – are US citizens. And at this point such people who don’t live in America can get a little over excited. I can work in America woohoo. No green card or resident alien stuff for me! Transiting through LAX will be a breeze.

All true. But much like the British Royal Family – US citizenship is also the gift that keeps on giving.

Now dear readers we have covered tax residence of individuals before. The tests that determine whether a country can tax on the foreign income of its inhabitants. And most countries have some version of the being here or owning stuff rule to work out whether someone is tax resident.

But thanks to American exceptionalism they go one step further. The US applies residence taxation to its citizens even the ones who don’t live there. So with foreign income and US citizens it is now possible to have the country of the source of the income, the country of ‘main’ residence and the US in the mix. So for Harry’s kids: with that Bermuda dosh: there could be Bermuda; United Kingdom and the United States all with their hand out. Just as well Bermuda not big on taxation. Such a relief. That is if Hazza pays tax in the first place.

Now for lesser New Zealand mortals who might be born in the US or have a Meghan Markle equivalent mum or dad: the US/NZ tax treaty is kinda important. And if they have income from any other country that country’s US treaty will also be your friend.

Because in all those treaties is a nifty little clause called Relief of Double Taxation. Aka such a relief – no double taxation. So let’s look a a situation where a New Zealand tax resident with a US born mum – NZUSM – earns $100 Australian interest income. Australia will deduct 10% tax or $10. New Zealand will also tax that income and another $23 ($33-$10) tax will be paid in New Zealand.

Then – because who doesn’t love a party – so will the United States. Giving an Australian tax credit of $10 and a New Zealand tax credit of $23. Depending on the US tax rate for the NZUSM – they will have to pay more tax; pay no more tax; or get surplus credits to carry forward.

Now for something like interest or any other income source New Zealand taxes; this is just annoying. Maybe a bit more tax to pay but not the end of the world.

The full horror comes when NZUSM has types of income that the US taxes but NZ doesn’t. You know like capital gains? Taxable in the US. And the horror becomes squared when NZUSM realises that the US uses its – not NZ’s – tax rules and classifications to calculate the income. Who would have thought?

So that look through company or loss attributing qualifying company where income has been taxed in hands of shareholders – treated as company the US – maybe not so clever after all. Coz what about a LTC loss that was offset against the taxable income of NZUSM – coz it is all like the same economic owner? US – no loss offset allowed – full tax now due. In the US the LTC is discrete NZ company. Nothing to do with NZUSM.

And then of course there is FATCA. For like ever the US has a requirement that its foreign based citizens report their balances with foreign banks. Now quelle surprise – compliance wasn’t great. So the US then said they would collect the information from the foreign banks directly and if they didn’t comply they’d impose a 30% tax on fund flows from the US. Did concentrate the mind somewhat.

Now the US is using this information to enforce compliance. And the NZUSMs of the world are not best pleased. Finding out there was a dark side – albeit one pretty well known – to the whole I can work in the US thing. Unsurprisingly there is a wave of people seeking to renounce their citizenship. Alg except the tax thing goes on for ten years after such renunciation. And such renunciation can’t be done by parents for their children.

So while Harry may have finally found his bride; he has also found the US tax system. What could possibly go wrong?

Andrea

No accounting for tax

Let’s talk about tax.

Or more particularly let’s talk about accounting tax expense.

Now dear readers the most unlikely thing has happened. A tax free week in the media. No Matt Nippert on charities – just for the moment I hope – no Greens on foreign trusts. No negative gearing and – thankfully – no R&D tax credits. So with nothing topical atm – we can return to actually useful and non-reactive posts. And yes I am the arbiter of this. Although the whole Roger Douglas and his #taxesaregross does warrant a chat. Need to psyche into that a bit first though.

So I am now returning to my guilt list. Things I have been asked to write about but haven’t . That list includes land tax; estate duties; some GST things; raising company tax rate; minimum taxes; and accounting tax expense.

And so today picking from the random number generator that is my inclination – you get accounting tax expense.

At the Revenue when reviewing accounts one of the things that gets looked at is the actual tax paid compared to the accounting income. This percentage gives what is known as the effective tax rate or ETR. And yes there are differences in income and expense recognition between accounting and tax but for vanilla businesses – in practice – not as many as you would think.

Now it is true that a low ETR can at times be easily explained through untaxed foreign income or unrealised capital profits. But it is also true that for potential audits it can be a reasonable first step in working out if something is ‘wrong’. Coz like it was how the Banks tax avoidance was found. They had ETRs of like 6% or so when the statutory rate was 33%.

So when I ran into a May EY report that said foreign multinationals operating in New Zealand had ETRs around the statutory rate – I was intrigued.

Looking at it a bit more – it was clear that it was a comparison of the accounting tax expense and the accounting income. Not the actual tax paid and accounting income. Now nothing actually wrong with that comparison but possibly also not super clear cut that all is well in tax land.

And I have been promising/threatening to do a post on the difference between these two. So with nothing actually topical – aka interesting – happening this week; now looks good.

Now the first thing to note is that the tax expense in the accounts is a function of the accounting profit. So if like Facebook NZ income is arguably booked in Ireland – then as it isn’t in the revenues; it won’t be in the profits and so won’t be in the tax expense.

Second thing to note is that the purpose of the accounts is to show how the performance of the company in a year; what assets are owned and how they are funded. One key section of the accounts called Equity or Shareholders funds which shows how much of the company’s assets belong to the shareholders.

And the accounts are primarily prepared for the shareholders so they know how much of the company’s assets belong to them. Yeah banks and other peeps – such as nosey commentators – can be interested too but the accounts are still framed around analysing how the company/shareholders have made their money.

And it is in this context that the tax expense is calculated. It aims to deduct from the profit – that would otherwise increase the amount belonging to shareholders – any amount of value that will go to the consolidated fund at some stage. Worth repeating – at some stage.

First a disclaimer. When IFRS came in mid 2000s the tax accounting rules moved from really quite difficult to insanely hard and at times quite nuts. Silly is another technical term. That is they moved from an income statement to a balance sheet approach. Now because I am quite kind the rest of the post will describe the income statement approach which should give you the guts of the idea as to why they are different. Don’t try passing any exams on it though.

Now the way it is calculated is to first apply the statutory rate to the accounting profit. And it is the statutory rate of the country concerned. That is why it was a dead give away with Apple – note 16 – that they weren’t paying tax here even though they were a NZ incorporated company. The statutory rate they used was Australia’s.

Then the next step is to look for things called ‘permanent differences’. That is bits of the profit calculation that are completely outside the income tax calculation. Active foreign income from subsidiaries; capital gains and now building depreciation are but three examples. So then the tax effect of that is then deducted (or added) from the original calculation.

For Ryman – note 4 – adjusting for non-taxable income takes their tax expense from from $309 million to $3.9 million. That number then becomes the tax expense for accounting.

But there is still a bunch of stuff where the tax treatment is different:

- Interest is fully tax deductible for a company. But – if that cost is part of an asset – it is added to the cost of the asset and then depreciated for accounting. And the depreciation will cause a reduction in the profits over say – if a building – 40-50 years. So for tax interest reduces taxable profit immediately while for accounting 1/50th of it reduces accounting profits over the next 50 years.

- Replacements to parts of buildings that aren’t depreciable for tax can – like interest – receive an immediate tax deduction. But for accounting a new roof or hot water tank are added to the depreciable cost of the building and written off over the life of the asset.

- Dodgy debts from customers work the other way. Accounting takes an expense when they are merely doubtful. But for tax they have to actually be bad before they can be a tax deduction.

These things used to be known as timing differences as it was just timing between when tax and accounting recognised the expense.

And then the difference between the actual cash tax and the tax expense becomes a deferred tax asset or liability. It is an asset where more tax has been paid than the accounting expense and a liability where less tax has been paid than the expense.

And the fact that these two numbers are different does not mean anyone is being deceptive. They just have different raisons d’etre. Now if anyone wants to know how much actual tax is paid – the best places to look are the imputation account or the cash flow statement. The actual cash tax lurks in those places.

But yeah it does look like actual tax. I mean it is called tax expense.

Your correspondent has memories of the public comment when the banking cases started to leak out. I still remember one morning making breakfasts and school lunches when on Morning Report some very important banking commentator was talking. He was saying that the cases seemed surprising coz looking at the accounts the tax expense ratio seemed to be 30%. [33% stat rate at the time]. But that 3% of the accounting profits was still a large number and so possibly worthy of IRD activity.

Dude – no one would have been going after a 3% difference.

In those cases conduit tax relief on foreign income was being claimed on which NRWT was theoretically due if that foreign income were ever paid out. So because of this the tax relief being claimed never showed up in the accounts as it was like always just timing.

Except that the wheeze was there was no actual foreign income. It was all just rebadged NZ income. And yeah that income might be paid out sometime while the bank was a going concern. So it stayed as part of the tax expense. Serindipitously giving a 30% accounting effective tax rate while the actual tax effective tax rate was 6%.

And a lot of these issues are acknowledged by EY on page 13 of under ‘pitfalls’.

So yeah foreign multinationals – like their domestic counterparts – may well have accounting tax expense ratios of 28%. But whether anyone is paying their fair share though – only Inland Revenue will know.

Andrea

Deregos

Let’s talk about tax.

Or more particularly let’s talk about the tax rules for deregistering charities.

It has been a big intellectual week for your correspondent. Tuesday night White Man Behind a Desk. No tax. An interesting riff on immigration that Michael Reddell clearly wasn’t the tech checker for. Wednesday night Aphra Green Harkness Fellow on US criminal justice reform coz States just ran out of money. I tried to run an argument that this was the good side of low taxes. Didn’t resonate – go figure. And Wednesday morning – Roger Douglas on turning taxes into savings coz #taxesaregross.

And it was on the lovely Roger I planning to write but on Friday was the Greens on how there were bugg@r all foreign trusts reregistering. So I thought I’d write about that and the genius decision to require disclosure rather than taxation.

And as if that wasn’t enough. Saturday morning the latest Matt Nippert on a US and charities thing. An elderly couple with no heirs wanting to transfer wealth to a charitable institution – awh lovely. So nice they chose NZ. But also Panama, low distributions and references to the IRS. Ok. Initial reaction was it looks like FATCA avoidance coz NZ charities are outside its scope of reporting to IRS. Really must get on to my ‘US citizenship is not a good thing for tax’ post. It has been in the can for longer than this blog has been running. So embarrassed.

But one thing really caught my eye. The charities had voluntarily deregistered. Mmm interesting.

Your correspondent now moves a tiny bit in the Charities NGO sector. And from time to time I hear ‘should we stay a charity? Coz need to be careful over advocacy and ActionStation isn’t a charity and it is alg for them.’

To which I try to reply in my best talking to Ministers language: ‘ That’s one option. It would mean handing over a third of your reserves in taxes or all of your reserves to another registered charity. But totes – if that is what you want.’

Strangely the conversation doesn’t continue.

Coz the law changed in 2014 to stop the rort of charities getting lots of lovely tax subsidised donations, not distributing; deregistering and then keeping all that lovely taxpayer dosh for themselves. Go Hon Todd!

Now on the face of it this should apply to our friends here very soon. Section HR 12 applies a year after deregistration and turns the reserves – less wot go to another charity – into taxable income.

Except there doesn’t seem to be anything explicit that makes it New Zealand source income. Possibly personal property or maybe indirectly sourced from New Zealand. But the source rules are kind of old school and want to bite on real stuff not deemed income. No matter how worthy of New Zealand source taxing rights it should be.

And of course none of this matters dear readers if the entity is New Zealand resident. Coz everything gets taxed! And as the trustees are a New Zealand company – high chance it will be. So alg.

Well almost.

Coz if the dosh in the charity all came completely from non-residents – the trust rules make it a foreign trust. And foreign source income aka income wot doesn’t have a New Zealand source is not taxed. So initial view – unless the source rules can bite on this deemed income or the trust isn’t a foreign one – there will be no wash up for our friends here.

Now on one level that is cool. The final tax was all about clawing back the tax benefits given on the initial donations and the charitable tax exemption on income. Here it would have been tax exempt anyway. So alg.

The other argument is that these guys intentionally registered as a New Zealand charity. Got all the good stuff like potentially non- disclosure to IRS as well as being to say they are a legit NZ charity. But now don’t get the bad stuff.

And NZ gets the bad name but not the income. What does that sound like? Oh yes the NZ Foreign Trust rules.

So glad that – according to the Greens – is coming to an end. Shame it had to be such a resource intensive way of doing it.

Andrea

Do ron ron

Let’s talk about tax.

Or more particularly let’s talk about the recent Australian transfer pricing case Chevron.

In a week when Inland Revenue announced a major restructure which will involve staff now needing ‘broad skill ranges’; it made me think of the type of work I used to do there – international tax.

It was true that my job needed skills other than technical ones:

- keeping your cool when being verbally attacked by the other side;

- being able to explain technical stuff to people ‘who don’t know anything about tax’ – aka anyone at Inland Revenue not in a direct tax technical function;

- ensuring the bright young ones got opportunities and didn’t get lost in the system; and

- generally ‘leveraging’ my networks to support those who were doing cutting edge stuff but not getting cut through doing things the ‘right’ way.

But otherwise what I did required a quite narrow specialised technical skill range. And that was good as it allowed me and my colleagues to focus on one particular area so we could be credible and effective. You know kinda like professional firms do?

As an aside I am not sure how this broad skill ranges thing ties in with the original business case – page 36 – which alluded to the workforce becoming more knowledge based. Coz knowledge-based work is kinda specialised not broad. But then the proposals are coming from a Commissioner who has a legal obligation to protect both the integrity of the tax system as well as the medium to long term sustainability of the department so I am sure she knows what she is doing.

Wonder what the penalties are for breaching those provisions? But I digress.

Back to me. The international tax I did though was actually quite broad compared to the work my colleagues did in transfer pricing. That was eye wateringly specialised and quite rightly so. These were the girls and boys who were on the frontline with the real multinationals like Apple, Google, Uber and the like.

And I was thinking of them recently when an appeal from an Australian transfer pricing case Chevron came out. Two wins to the Australian Commissioner and the Australian TP people – woop woo! Go them.

The guts of the case is that Chevron Australia set up a subsidiary in the US which borrowed money from third parties for – let us say – not very much and on lent it to Chevron Australia for – let us say – loads. And it was with a facility of 2.5 billion US dollars. Now you can kinda imagine the difference between not very much and loads on that was a f$cktonne of interest deductions – see why I get obsessed with interest – and therefore profit shifting from Australia to the US.

Now even though it was a subsidiary of Chevron Australia; the Australian CFC rules don’t seem to apply to the US. Coz comparatively taxed country – thank god we don’t have those rules anymore. And the judgment says it wasn’t taxed in the US either. Didn’t spell out why but I am guessing as the Australian companies are Pty ones – check the box stuff – they get grouped in the US somehow. No biggie for US but bucket loads less tax than they would otherwise pay in Australia.

And according to Chevron it was like totes legit. Coz loads is the market price for lots of really risky unsecured debt. I mean seriously dude like look up finance theory.

To which the seriously unbroad people in the Australian Tax Office said – yeah nah. Theory is like only part of it. The test is what would happen with an independent party in that situation.

- Option one – the seriously risky party ponies up with guarantees from those who aren’t seriously risky. You know how those millennials who buy houses and don’t eat smashed avocado do when their parents guarantee their loans? It is the same with big multinationals.

- Option two – banks don’t lend. So just like for all the milennials who don’t own houses but who do eat smashed avocado and don’t have rich parents.

And the Australian court thought about it all – pointed at the unbroad public servants – and said:

“What they said. Chevron you are talking b%llcocks. The arms length price is one an independent party like millennials would actually pay. This includes guarantees and you price on those facts. Not the fantasy nonsense you are spouting.”

Well broadly. Actual wording may vary. Read the judgments.

Now these are seriously useful judgments – internationally – for the whole multinationals paying their fair share thing. Let’s just hope New Zealand keeps the people who can apply them.

Andrea

Cry me a river

Let’s talk about tax. Yes dear readers – tax. No prison reform no yoga stuff. Just nice emotionally simple tax.

Or more particularly let’s talk about the recent Australian Budget announcement of a levy on banks aka the Great Australian Bank Robbery.

Your correspondent has now completed her yoga teacher training and so is available for weddings, funerals and bar/bat mischvahs. Highlights of the course included injuring herself while dancing and getting zero on the first attempt on the final exam.

It’s not like I haven’t failed things before but when the question was – reminiscent of the Peter Cook coal miners sketch – ‘who am I?‘ to fail – mmm – more than a little surreal. Now even the first time thought I had answered in a sufficiently right brained way – lots of introspective emotion involving personal power and connection with others – aahhh no.

But your correspondent is a resilient adaptive individual – even before the course – so regrouped with – ‘complete‘.

90%.

I couldn’t make this up. Subsequently found other correct answers included: me; enough – and my particular favourite – light. Ok right. Thanks for sharing.

And it all really did make me crave balance. Which in my world after eight full days on yoga is the left-brained world of tax. I had planned to write about the Australian transfer pricing case Chevron but this week has been the Australian Budget with a big new tax on their banks. And as I have had a few questions on this and I am trying to be more topical – here we go:

Now the bank tax thing seems to be part of a package of the Australian government responding to the Australian banks bad – but probs more likely monopolistic – behaviour. Also potentially a political response to appointing a popular Labour Premier – and good god a woman – to be head of the Bankers Association. And my word the banks must have been bad as they only found out about it on Budget Day and it starts on 1 July without – as far as I can see – any grandfathering.

Wow. Just wow.

So what is it?

It is a levy on big banks liabilities that aren’t:

- customer deposits or

- (tier 1) equity that doesn’t generate a tax deduction.

It targets commercial bonds, hybrid instruments (tier 2 capital) and other instruments that smaller banks can’t access coz they are small. And as it will form part of the cost of this borrowing- under normal tax principles – the levy would be tax deductible. But even allowing for this tax deduction it is supposed to raise AUD 6.2 billion over four years. So not chump change.

What is its effect?

Now there can be no argument that the levy will effectively make such instruments more expensive to use. And here the public arguments get really sophisticated:

- Malcolm Turnbull says that ‘other countries have them’ and it would be ‘unwise’ for banks to pass it on to borrowers; and

- the Treasurer Scott Morrison (ScoMo) is telling banks to ‘cry me a river’ when they have expressed a degree of displeasure.

Awesome. Thanks for playing.

Corrective taxation

Now while this is predicted to raise revenue; it is by no means clear that this is its primary objective or even if it will occur. The reason being it only applies to big banks and to certain types of liabilities. To me this looks like a form of corrective tax like cigarette excise rather than a revenue raiser like an income or consumption tax like GST.

And much like a tax on cigarettes; pollution or congestion; this tax is 100% avoidable – legitimate tax avoidance even – by funding lending with an untaxed option like customer deposits. In theory anyway. It is likely that banks will have maxxed out how much they can borrow from the public at existing interest rates.

But with this extra tax; the relativities will change. Meaning there is now scope to pay more for the untaxed deposits but less than the tax if Banks want to maintain the same level of lending. Bank costs will still go up but through marginally higher deposit rates incentivised through the tax – rather than the tax itself.

In this scenario the Australian government still gets the costs of the higher interest deduction but not the revenue. But Australian savers win.

As the big banks are the dominant players in the market – this increase in interest rates for depositors will also impact the smaller banks as they will need to pay the higher rates to continue to attract depositors too. So no actual competitive pressure from the small banks and possibly less actual tax. Genius.

An alternative equally revenue enhancing scenario is that banks wind down assets – lending – and become smaller. Less lending but higher cost of borrowing if demand stays the same.

Who bears the cost?

As they do in New Zealand anytime extra taxes are mooted; the Australian banks are arguing that these extra costs will be borne by borrowers. Now in a fully competitive market without barriers to entry the more price dependent – or elastic – the demand for loans is the more it will fall on the shareholders. But lending overall will fall with the imposition of a tax which in turn will have housing market impacts if fewer people can get a mortgage.

With barriers to entry – like hypothetically say banking regulation – they are already pricing to maximise their profit so I would be inclined to say it will also hit shareholders. And the fall in price of banking shares would indicate that is what shareholders think too.

Except that if deposit rates go up instead; the cost structure of the entire banking industry will go up. And if no tax is actually being paid but the cost is being transferred through higher deposit rates then the banking industry will have political cover to pass the cost on to borrowers.

Alternatives

Now if this schmoozle is all about the banks paying more tax then either a higher company tax rate on big banks or increasing the requirements for non- interest bearing capital would have been far simpler. While the former is pretty transparent that it is a blatant tax grab from the banks; the latter less so. They both have the advantage though of ensuring tax can’t be opted out of as well as keeping the competitive pressure from the smaller banks.

But both would form part of the banks cost structure and so – depending on the pressure from the small banks and how elastic demand is – be passed on in some form to borrowers. However if the government really wanted only the shareholders to pay then a one- off windfall tax would be the way to do it.

Whether or not the banks – and their shareholders – should actually be treated like this is another story. But Cry me a river ScoMo: at least be transparent and do it properly!

Other stuff

It goes without saying that this is truly cr@p process. All the detail seems to be in ScoMo’s press statement. Although – legislation by press statement – is an unfortunate feature of Australian tax policy.

And as for the Malcolm Turnbull ‘other countries have it too’ argument. From what I can see this was to pay back the government for the bail outs they gave the banks over the GFC. While Australia does have deposit insurance I wasn’t aware of any like actual bailouts.

It is though kinda reminiscent of the diverted profits tax which is also a targetted tax on a group of bad people. Except that might have a non-negative tax effect. Here we have – to extent it is passed on in higher deposit rates – higher costs industry wide causing less, not more, tax paid by this industry. Let’s just hope for Australia’s sake the savers are not all in the tax free threshold.

So nicely done ScoMo and Big Malc. Possibly more Lavender Hill mob than Ronnie Biggs. But much like the Australian fruit fly; keep it on your side on the Tasman. It makes even this revenue protective commentator blanch and our banking tax base can so do without it.

Andrea

Update

A commentator on the blog’s facebook page has suggested that this levy makes sense in terms of addressing the huge implicit subsidy that is the Australian deposit guarantee scheme. I have absolutely no issue with this being charged for in the form of a levy on the banks. Naively I would have thought that such a levy would then be based on the deposits covered by the guarantee not the liabilities that aren’t. Apparently that’s not how Australian politics works!

The discussion can be found in the Facebook comments section for this post.